2020 Geospatial Competency Assessment - Industry Input

Introduction

This research study uses Q Methodology to assess the perceptions of respondents towards the core competencies contained within the National Geospatial Technology Center of Excellence (GeoTech Center) Geospatial Competency Matrix.

Problem Statement

There has historically been a lack of external input from geospatial practitioners regarding their views towards geospatial competencies. What input there was did not force participants to discriminate between the relative importance of the competencies and sought input from the field as a whole, without consideration of occupation.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of the study is to explore the viewpoints of geospatial practitioners toward the GeoTech Center Geospatial Competency Matrix and why they hold these views. By assessing the viewpoints of educators toward these competencies, the researcher can better understand how practitioners view core geospatial competencies.

Finding 1. This study revealed six viewpoints, representing the different perspectives of geospatial practitioners participating in the research project. The six documented factors characterize a substantial variation in the perceptions of technical geospatial competencies. The researcher developed a title, compiled characteristics, and constructed a descriptive narrative for each factor. The emergent factors were Factor 1: We Perform Technician-level Tasks; Factor 2: We Reveal Spatial Relationships to Solve Problems; Factor 3: Remote Sensing is Crucial; Factor 4: Databases are Our Mission; Factor 5: Managing the Integrity of Data; and Factor 6: Preparing Vector Data for Analysis.

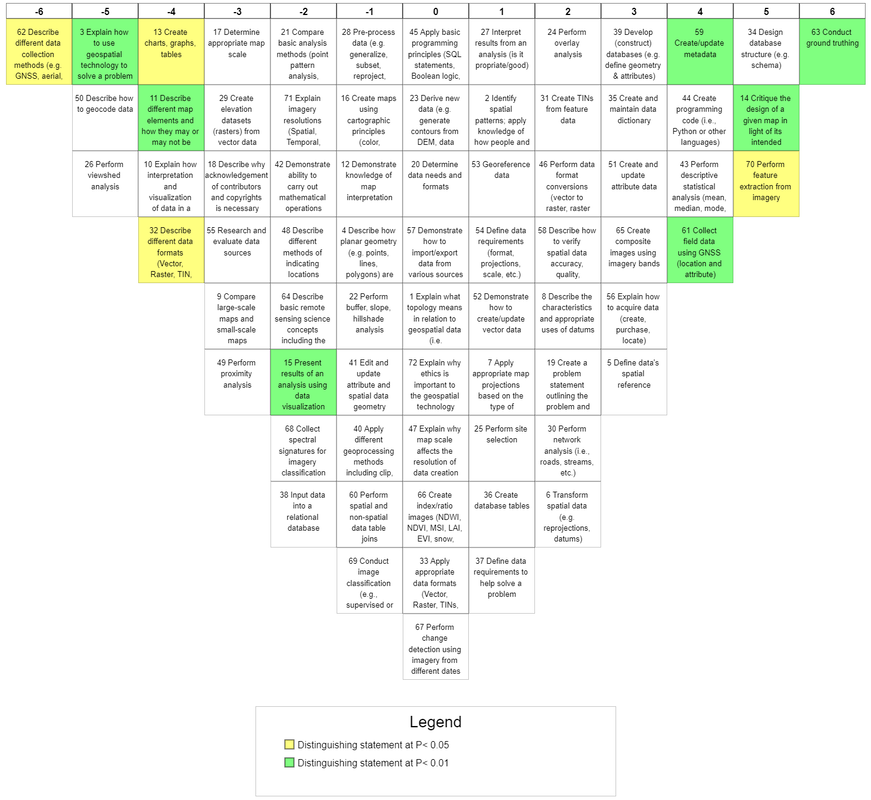

Finding 2. The respondents shared some general impressions regarding the perceived relevance of the statements located within the GeoTech Center Geospatial Competency Matrix. The values discussed here represent the original sorting scheme (-6 to +6) and ranged from 2.49 to -2.90 (see Appendix D). The range in value was 5.39, much less than a possible range (-6 to +6), and suggested a compressed data set. Furthermore, the respondents generated no consensus statements between the factors, which is not surprising, given the generation of six factors. No competency cluster dominated the most relevant skills, represented by positive scores. Positively viewed competency areas included using geospatial science to solve problems, cartographic principles, and data management. The participants negatively viewed competency areas related to digital imagery and remote sensing. Seven of the lowest scoring nine competencies were associated with this area of the geospatial domain. These statements' mean values were -2.07, with the only outlying competency connected with remote sensing, Statement 70 garnering a -.080 score.

Conclusion

This study represented the results of an investigation to address how geospatial practitioners view the geospatial competency statements located within the GeoTech Center Geospatial Competency Matrix. The researcher collected data from 41 geospatial practitioners, with 27 respondents loading onto six factors. The study gathered demographic, Q-sort (quantitative), and narrative (qualitative) data. To address the research question (How do geospatial practitioners view the geospatial competency statements located within the GeoTech Center Geospatial Competency Matrix, and why?), the researcher performed factor analysis on the Q-sort submissions and generated six factors. The post-sort questionnaire provided additional information and critical insight to the researcher, who used the qualitative data to build the narratives for each factor. The themes developed from the analysis include Factor 1: We Perform Technician-level Tasks; Factor 2: We Reveal Spatial Relationships to Solve Problems; Factor 3: Remote Sensing is Crucial; Factor 4: Databases are Our Mission; Factor 5: Managing the Integrity of Data; and Factor 6: Preparing Vector Data for Analysis. The investigation revealed distinct opinions relating to peripheral disciplines' relevance (remote sensing and digital imagery). The study discovered no consensus statements, which may not be surprising given the presence of six factors. The lack of shared statements may demonstrate the diversity of views, derived from the variety of users, expressed across the factors.

Introduction

This research study uses Q Methodology to assess the perceptions of respondents towards the core competencies contained within the National Geospatial Technology Center of Excellence (GeoTech Center) Geospatial Competency Matrix.

Problem Statement

There has historically been a lack of external input from geospatial practitioners regarding their views towards geospatial competencies. What input there was did not force participants to discriminate between the relative importance of the competencies and sought input from the field as a whole, without consideration of occupation.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of the study is to explore the viewpoints of geospatial practitioners toward the GeoTech Center Geospatial Competency Matrix and why they hold these views. By assessing the viewpoints of educators toward these competencies, the researcher can better understand how practitioners view core geospatial competencies.

Finding 1. This study revealed six viewpoints, representing the different perspectives of geospatial practitioners participating in the research project. The six documented factors characterize a substantial variation in the perceptions of technical geospatial competencies. The researcher developed a title, compiled characteristics, and constructed a descriptive narrative for each factor. The emergent factors were Factor 1: We Perform Technician-level Tasks; Factor 2: We Reveal Spatial Relationships to Solve Problems; Factor 3: Remote Sensing is Crucial; Factor 4: Databases are Our Mission; Factor 5: Managing the Integrity of Data; and Factor 6: Preparing Vector Data for Analysis.

Finding 2. The respondents shared some general impressions regarding the perceived relevance of the statements located within the GeoTech Center Geospatial Competency Matrix. The values discussed here represent the original sorting scheme (-6 to +6) and ranged from 2.49 to -2.90 (see Appendix D). The range in value was 5.39, much less than a possible range (-6 to +6), and suggested a compressed data set. Furthermore, the respondents generated no consensus statements between the factors, which is not surprising, given the generation of six factors. No competency cluster dominated the most relevant skills, represented by positive scores. Positively viewed competency areas included using geospatial science to solve problems, cartographic principles, and data management. The participants negatively viewed competency areas related to digital imagery and remote sensing. Seven of the lowest scoring nine competencies were associated with this area of the geospatial domain. These statements' mean values were -2.07, with the only outlying competency connected with remote sensing, Statement 70 garnering a -.080 score.

Conclusion

This study represented the results of an investigation to address how geospatial practitioners view the geospatial competency statements located within the GeoTech Center Geospatial Competency Matrix. The researcher collected data from 41 geospatial practitioners, with 27 respondents loading onto six factors. The study gathered demographic, Q-sort (quantitative), and narrative (qualitative) data. To address the research question (How do geospatial practitioners view the geospatial competency statements located within the GeoTech Center Geospatial Competency Matrix, and why?), the researcher performed factor analysis on the Q-sort submissions and generated six factors. The post-sort questionnaire provided additional information and critical insight to the researcher, who used the qualitative data to build the narratives for each factor. The themes developed from the analysis include Factor 1: We Perform Technician-level Tasks; Factor 2: We Reveal Spatial Relationships to Solve Problems; Factor 3: Remote Sensing is Crucial; Factor 4: Databases are Our Mission; Factor 5: Managing the Integrity of Data; and Factor 6: Preparing Vector Data for Analysis. The investigation revealed distinct opinions relating to peripheral disciplines' relevance (remote sensing and digital imagery). The study discovered no consensus statements, which may not be surprising given the presence of six factors. The lack of shared statements may demonstrate the diversity of views, derived from the variety of users, expressed across the factors.

This research study validates using a Q Methodological study as a practical approach to examining the statements within a competency model. Moreover, it demonstrated a process using industry representatives to evaluate a conceptual model of competencies. The results of this study provided feedback from geospatial practitioners regarding how they perceive the competencies in the GeoTech Center Geospatial Competency Matrix. Better sources of data analysis, such as that found in this study, could enable educational institutions to more effectively engage industry partners and increase the value of their instruction to potential members of the geospatial workforce.